What is ICH?

ICH stands for:

The International Council (previously Conference) for Harmonisation

of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use.

The mission of ICH is to “achieve greater harmonisation in the interpretation and application of technical guidelines and requirements for product registration, thereby reducing duplication of testing and reporting carried out during the research and development of new medicines.”

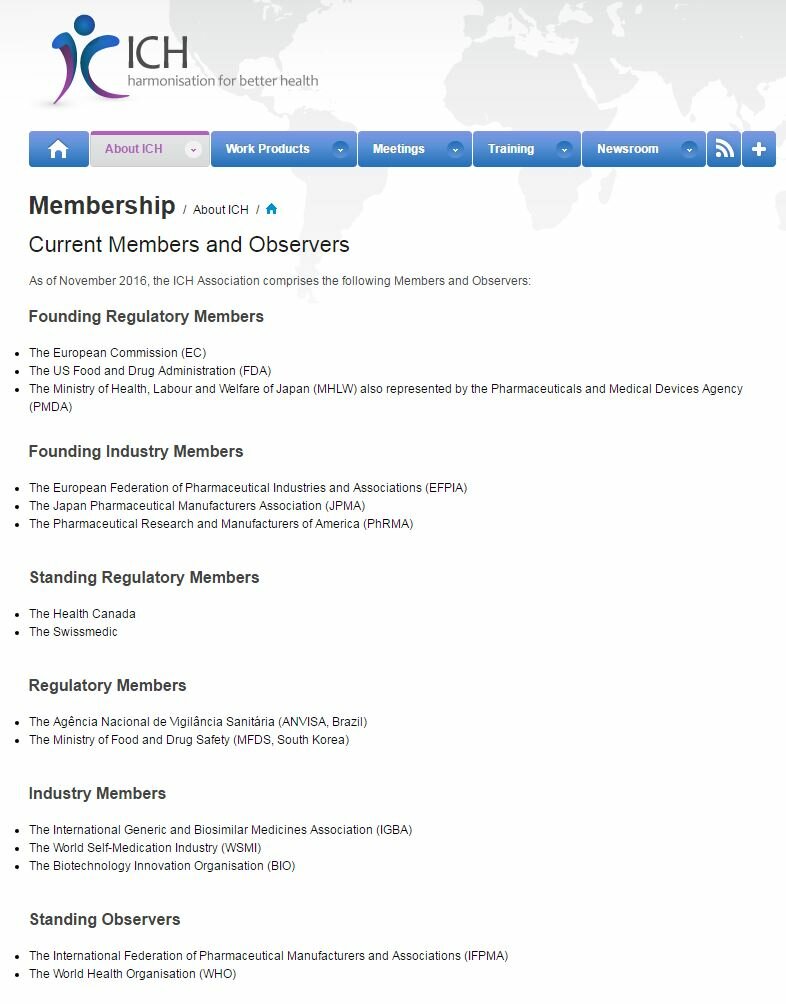

Created 25 years ago, its membership reflects its mission to harmonise across regions the regulatory approval process for new drugs developed by industry (text reproduced from ICH’s website):

The fundamental problems with ICH

For many of the roles of ICH, for example, pharmaceutical manufacturing and testing, just involving drug regulators and industry might be entirely appropriate, but it is not appropriate for the conduct of randomised trials. This is because trials are the concern of multiple parties, certainly not just regulators and industry but also others. Most notably CTTI has clearly demonstrated that it is feasible to engage all of the relevant parties in dialogue and discussion on how trials can be improved. ICH by contrast shows no willingness to engage with all of the parties, not least trial participants and the public.

One of us (Trudie Lang) does randomised trials in low-income countries in sub-Saharan Africa, so when local collaborators ask, “why do we have to follow this ICH-GCP guideline with all of these extra forms and expense?” how should she best respond? The trial is not being conducted by industry for a new drug registration and it’s not being conducted in a country that is part of ICH. The trial might not even be testing a drug at all! There isn’t a good answer.

Although publicly funded by the various regulatory authorities, ICH operates in a closed and non-transparent manner seemingly only listening to the voice of the parties listed on the ICH website above, namely the various regulatory authorities and industry.

When we have repeatedly tried to engage with ICH we are largely ignored or, if we get a response, we are directed to discuss our concern with our regulatory authority. For example, when we heard that ICH planned to update the ICH-GCP guideline and had created a working group to take it forward we asked who was on the group we never received a response. When ICH announced the recent update to the ICH-GCP guideline there were no details about the people involved. Who was involved? What trials have they done?

Why we now believe that ICH who created the problem that is the ICH-GCP guideline will be unable to be the solution to make it much easier to do randomised trials

So, for all of these reasons above; only listening to the voice of drug regulators and industry, ignoring everybody else, including patients and the public (who it still insists on calling “subjects”), not being truly global and, most importantly, the fundamental problems with the ICH-GCP guideline and the problems it has created, we now believe that ICH is not be the best body to take things forward.

But, as outlined on the next page, it has now become clear that while ICH has finally acknowledged the problems caused by its own guidance, it is unable to acknowledge the fundamental problems with it by insisting that the original text in the guideline “is still correct.”

In the final analysis, you are either part of the problem or part of the solution and ICH with its unwillingness to properly engage with those involved in trials and its insistence that the ICH-GCP guideline is still correct clearly demonstrates that we have a two fold problem here, namely the ICH-GCP guideline and ICH itself.

As a reality check, the question we think that it is worth asking is if randomised trials were invented today would we do them like this?

Let’s now take a closer look at the document that has caused so many problems, the ICH-GCP guideline .