Why making it much harder to do randomised trials really matters

Consider this scenario. A patient goes to see their family doctor to get the results from a recent health-check. The doctor informs them that their blood-pressure is high, which along with other risk-factors puts them at high-risk of having a heart-attack, so would like to prescribe them a blood-pressure lowering drug. So far, so good. However, the doctor knows that there are a few different drugs that they could prescribe, which have similar effects, so what do they decide to do?

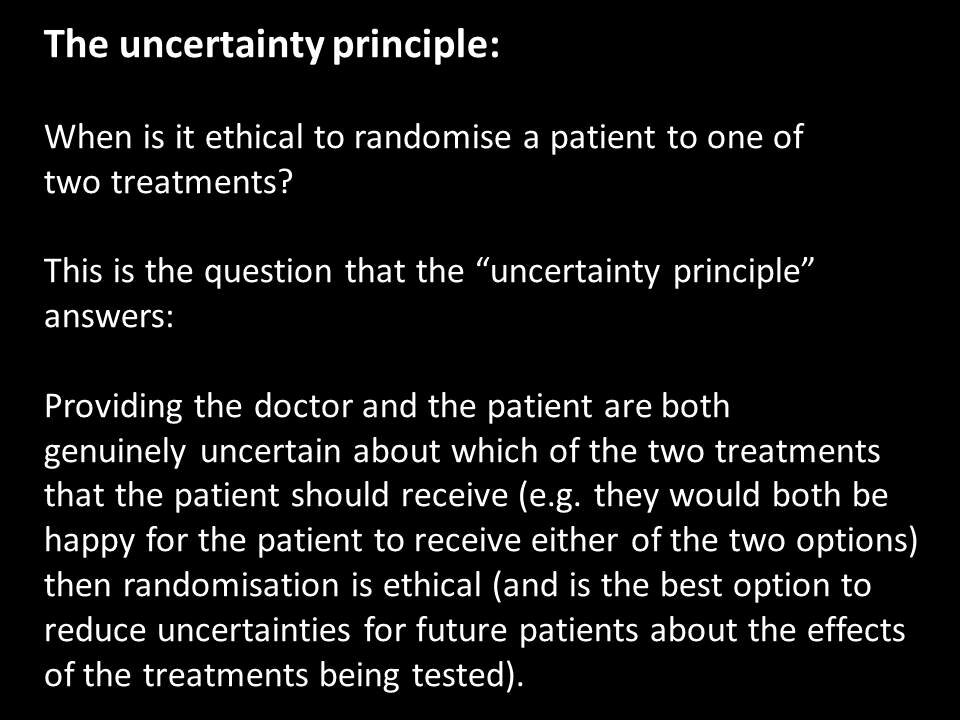

Let’s to keep things simple assume that the doctor can not decide which of two drugs to prescribe to that patient? They might check the prescribing information for both of the drugs and see if that helps, but let’s say they’ve done that and are still uncertain about which one to prescribe. They might then decide to prescribe the cheapest one or they might just pick one, say the first one listed on their computer screen, as the evidence suggests that it doesn’t really matter. These kinds of genuine uncertainties about the effects of treatments are much more common in medicine than most people assume.

Instead, let’s repeat this scenario and instead of the doctor just picking one of the two drugs at random for that patient, instead they ask the question, is there a study, a randomised trial comparing these two drugs?

If there is, they are genuinely uncertain about which drug to prescribe so inform the patient of this and then invite them to take part. If the patient is happy to take part then that would be recorded and the drug which they are prescribed would be decided by central randomisation (which can be easily done on a computer).

It’s not unreasonable to assume that many other doctors treating similar patients have the same uncertainties about which of these two treatments to prescribe. This means we have the basis for doing a randomised trial, but in the first scenario above, where the doctor just picks one of the drugs to prescribe, we learn nothing about the comparative effects of the two treatments, but in the second scenario, where the patient takes part in a randomised trial, we will when enough patients have been randomised be able to address the question of whether one of these treatments is better for the treatment of similar patients?

Let’s for the sake of simplicity assume that 50,000 patients need to be treated to address this question. While that is a large number, when that number have been recruited to the trial comparing those two treatments we will have reliably addressed that question and can move on to addressing another unanswered question. When the doctor just picks one of the treatment we unsystematically treat 50,000 patients, don’t address the uncertainties about the two treatments, so what we do, treat another 50,000 patients and so on and so on…….i.e. we learn nothing!

Now, both drugs are licensed for use in these patients so the doctor can just pick one to prescribe, but it is obviously better to enrol the patient in a randomised trial. As the treatments being compared in the trial are being used in the usual way there is no need for things like extra tests, visits or lengthy forms to complete. So, why don’t simple trials like this get done?

Inappropriate barriers to the much more widespread conduct of randomised trials

Ask anybody who is responsible for regulating and governing research what there first responsibly is and without hesitation they will respond “to protect patients.”

Now, we have no argument with this as the starting principle and from this then having proportionate and sensible regulation, but what we need to recognise is that most research regulation and governance makes it much more difficult to do research, studies like the trial described above and what this means is that we remain in the dark about the effects of treatments because the trials that should get done don’t. The outcome of this is that we’ve created regulation with the purpose of protecting people, but it is having exactly the opposite effect, namely exposing patients to risk from uncertainties about treatment persisting because of inappropriate barriers to randomised trials. The best example of inappropriate regulation acting as a barrier to research to address important uncertainties about treatments is the ICH-GCP guideline.

This is why we’ve created the MoreTrials campaign to make it much easier to do randomised trials by replacing the ICH-GCP guideline with a new modern set of principles for conducting trials developed by everybody with an interest in trials.

Finally, returning to the scenario above. One of us (Iain Chalmers) was actually involved in trying to set up a randomised trial just like the one described above with family doctors in the UK (this trial was comparing two drugs that lower-cholesterol). After a number of tries, the trial was eventually abandoned because of the numerous regulatory and other governance requirements. The main reason the trial ultimately failed was the requirements of the ICH-GCP guideline, particularly the requirement that the doctors were required to have training on the ICH-GCP guideline. Contrast this with the doctor who has no regulation or oversight in terms of which of the treatments they decide to prescribe. We think this double-standard is causing serious harm to all of us and needs to be changed.